|

|

Smeerenburg

[79° 40' N 11° 00' E]

By Øystein Overrein (ed.), Jørn Henriksen, Bjørn Fossli Johansen, Kristin Prestvold

The name “Smeerenburg” means “Blubber Town”. Its whaling station served as the main base for Dutch whaling in the first half of the 17th century, which was the period when whale hunting was still happening along the coastline and in the fjords of Svalbard. Smeerenburg is situated on the island of Amsterdamøya, surrounded by fjords, tall glacier fronts and steep, rugged mountains. The most obvious sign of its days as a whaling station are the large cement-like remains of blubber from ovens where the blubber was boiled. The rest of the old Smeerenburg has largely disappeared under layers of sand.

Remains of a blubber oven, where “blubber cement” outlines the area where cooking vessels used for rendering oil from the fat once stood. Blubber cement, a mixture of whale oil, sand and gravel, has a texture resembling asphalt. Bricks from the tryworks can also be found on this site, in and around the cement-like substance. It is not allowed to step on, or remove, the blubber cement, oven bricks or other remains of the whaling station. Visitors must restrict their steps to the outside of the circle. (Image: Bjørn Fossli Johansen / The Norwegian Polar Institute) Take care:

- Do not go ashore when the ground is moist due to the snow melting.

- Do not walk over the remains of the blubber ovens.

- Do not touch the blubber cement.

- Do not touch loose objects that are man-made (protected cultural remains)

- Do not tread on moist patches of step ground.

- Make sure there are no walruses on the beach when choosing where to go ashore.

Smeerenburg from the air. The old Smeerenburg was located out on the headland, to the bottom left in the picture. (Image: Kristin Prestvold / The Governor of Svalbard) Smeerenburg from the air. The old Smeerenburg was located out on the headland, to the bottom left in the picture. (Image: Kristin Prestvold / The Governor of Svalbard)

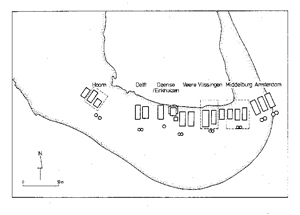

Map of Smeerenburg, which shows the location of each whaling facility and indicates the chambers of commerce that owned and operated them. The ovens from Amsterdam have either disappeared into the sea or are about to be washed away. This is the same fate that met the houses that were originally behind the ovens. (Reprinted with permission from L. Hacquebord, Arctic Centre, the University of Groningen, the Netherlands) Map of Smeerenburg, which shows the location of each whaling facility and indicates the chambers of commerce that owned and operated them. The ovens from Amsterdam have either disappeared into the sea or are about to be washed away. This is the same fate that met the houses that were originally behind the ovens. (Reprinted with permission from L. Hacquebord, Arctic Centre, the University of Groningen, the Netherlands)

In the summer of 1906, the Dutch cruiser Friesland came to Smeerenburg and Amsterdamøya to raise a memorial dedicated to the Dutch who lost their lives during the old whaling period. On Smeerenburgsletta they found areas with graves from the whaling period where the coffins had been pushed up from the ground due to frost, and where the crosses had fallen down. The Friesland crew gathered remains of skeletons and coffin boards and left them under a large pile of rocks. They erected a memorial here, for this new grave and the deceased, which says: "HMS Friesland repaired these graves in 1906 on order of the queen of the Netherlands" (“Hr. Ms. Friesland herstelde diese graven in 1906 op last van der Koningin der Nederlanden”). (Image: Bjørn Fossli Johansen / The Norwegian Polar Institute) In the summer of 1906, the Dutch cruiser Friesland came to Smeerenburg and Amsterdamøya to raise a memorial dedicated to the Dutch who lost their lives during the old whaling period. On Smeerenburgsletta they found areas with graves from the whaling period where the coffins had been pushed up from the ground due to frost, and where the crosses had fallen down. The Friesland crew gathered remains of skeletons and coffin boards and left them under a large pile of rocks. They erected a memorial here, for this new grave and the deceased, which says: "HMS Friesland repaired these graves in 1906 on order of the queen of the Netherlands" (“Hr. Ms. Friesland herstelde diese graven in 1906 op last van der Koningin der Nederlanden”). (Image: Bjørn Fossli Johansen / The Norwegian Polar Institute)

At the land end of the headland there are areas where moss tundra can be found. Because of the soil, other parts of the tundra are also vulnerable and should not be stepped on, especially when it is moist. It is advised not to visit Smeerenburg when the soil is particularly wet, such as during – and immediately after – the snow thawing. (Image: Bjørn Fossli Johansen / The Norwegian Polar Institute) At the land end of the headland there are areas where moss tundra can be found. Because of the soil, other parts of the tundra are also vulnerable and should not be stepped on, especially when it is moist. It is advised not to visit Smeerenburg when the soil is particularly wet, such as during – and immediately after – the snow thawing. (Image: Bjørn Fossli Johansen / The Norwegian Polar Institute)

Smeerenburg – myth and reality

Smeerenburg has a magical way of attracting you. No other station from the whaling periods in Svalbard has had nearly as much praise and mention as this legendary blubber town. Many myths and fabulous stories have been made up about its vitality and size: it was said to be a town bustling with people, with shops, bakeries, warehouses, a church and fortresses as well as bars and brothels. It is estimated that the town had thousands of inhabitants. Nansen (1920) described hundreds of ships mooring in the fjord, and a lively town, abundant in riches. He spoke of a town with stands and streets, where up to ten thousand people gathered in the summer in connection with the whaling. There were warehouse sheds and cooking facilities for blubber, gambling dens, smithies and workshops. And all along the flat beach there were lots of seafarers returning from whaling, and as many women, clad in varied colours, “hunting” for men. “And all this to provide oil to Europe; though even more to provide the ladies with hoops so they can ruin their bodies with corsets and hoop skirts” (Nansen, 1920).

The story of Smeerenburg began with a slow start in the years before 1620. In the beginning, the whaling station was only temporary, with simple and temporary blubber ovens used to boil the blubber on the beach. The work was carried out outside, with no shelter.

With time, Smeerenburg developed into a small settlement, with permanent, solid tryworks for rendering oil, residential houses, warehouses and workshops. There were also platforms for cutting strips of blubber and on which the coolers could be placed. Craftsmen, blubber cutters and blubber cooks lived in Smeerenburg temporarily throughout the whaling season.

In its heyday, the whaling station consisted of around 19 buildings. Most of the houses had floors as well as fireplaces, so the living conditions must have been quite good. The area between the houses was paved, and there were ditches to get rid of rain- and meltwater. By the ovens, superstructures sheltered workers from the worst of the weather.

All myths are doomed. Between 1979 and 1981 large archaeological excavations were carried out where the whaling station had been. The investigations led to a more nuanced and realistic picture of Smeerenburg. Contrary to the myth of a lively town that, at its peak, had up to 20,000 inhabitants, the settlement actually had approximately 200 inhabitants: all workers at the whaling station. The real Smeerenburg may be more boring than the myth, but it must still have been a place that was very lively when all the ovens were in use.

The ruins of Smeerenburg – a fragmented past

In the second half of the 17th century, Smeerenburg’s days as a whaling station drew to an end. The whales deserted the fjords and the station fell into disuse. The ovens were dismantled and whatever useful material this produced was taken away. Smeerenburg started the journey towards becoming a ruin fairly early – there were already signs of decay when Friedrich Martens came to visit in 1671. Several of the buildings had burnt to the ground. Still, Martens described buildings that were still standing there, although the material that was meant to be inside them had been removed over a course of several years, having been used as firewood and for repairing ships.

Even long after the station had been shut down, Smeerenburg continued to be used as an emergency harbour, as a place to store whaling equipment and as a place where the whaling vessels gathered in the spring and in the autumn. There were good harbour conditions in Smeerenburg, and many fairways led to the place. The ships could always get out into open waters should the drift ice suddenly enter the fjords. It was possible to find freshwater ashore and there was also an opportunity to put fresh meat on the menu before the long journey home. There was also a cemetery here. In Smeerenburg there are 101 graves belonging to men who lost their lives to whaling in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Vulnerable elementsThere has been wear and tear from people moving about both on the foundations and the blubber ovens in Smeerenburg. There is a thin layer of vegetation on the sandy ground and it wears down easily. The blubber ovens were built using heaps of sand, and these have largely disappeared, exposing the blubber cement. The blubber oven furthest out on the headland is particularly worn. Its sandy base has been washed away and only parts of the blubber cement remain. This is the reason why it is not allowed to walk on the remains of blubber ovens when you move about in Smeerenburg. It is necessary to be very cautious in this area and ensure that one is not damaging these cultural treasures further.

The area is occasionally used by walrus to haul-out. Make sure there are no walruses on the beach before going ashore here. Landing sitesThere are several landing sites to choose from, depending on the direction of the wind. The best place tends to be by the beacon, to the south of the headland.

Association of Arctic Expedition Cruise Operators (AECO) has visitor guidelines for Smeerenburg.

|

The Cruise Handbook is also available in book form

Order now

Hard cover with numerous pictures - 249 pages - NOK 249.00

Norwegian Polar Institute

Fram Centre

NO-9296 Tromsø

NORWAY

|

Norsk

Norsk